Corey and Sally are feeling pressure to make a decision because the credit expires at the end of April. I talked with them about their house plans the other day then had a follow-up conversation with a mutual friend of ours, Garth.

They're looking to buy a home for around $140,000, so on the surface the $8,000 looks like a compelling reason to buy now. The $8,000 credit is significant for Corey and Sally, so guaranteeing themselves a 6-percent savings isn't a bad way to start off. There is no guarantee they could get the seller (this is a pre-approved short sale on a bank owned property) to come down another 6-percent.

Garth wanted to make sure they'd considered all of their options and knew what they wanted in a home.

I agree with Garth's assessment around knowing what you want and considering options. Buying a home is far more than a financial decision. The place you will raise your kids, spend 1/2 of your time, and build your life is one of the most impactful decisions a couple will ever make.

Garth recommended our friends build a spreadsheet with all of the features and requirements they have in a home. The sheet should include everything from budget impact and square footage to location and school information.

Building a detailed spreadsheet with all of the features and home requirements will take a while and might slow down Corey and Sally's ability to get the home buyer credit.

Should they rush their decision?

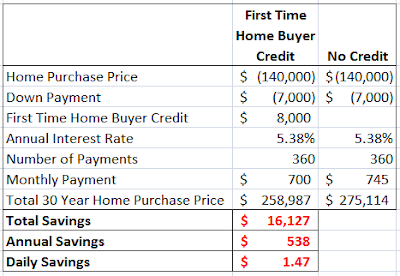

I ran a quick analysis to see how much they would really save by purchasing now versus taking their time. I considered purchase price, a 5-percent down payment, that they'd add the credit to their down payment if they got it, and a 30 year mortgage at their pre-approved rate.

By buying now and getting the credit they would save $16,127 over the life of a 30 year purchase, $538 per year, $45 per month, and $1.47 per day.

I don't think the savings are as much as my analysis shows. Some portion of the home buyer credit is currently built into starter home prices. By that I mean, once the credit expires home sellers are likely to lower their price (if not the advertised price, the contract price). The market as a whole has factored in the home buyer credit today and will have to factor it out after April 30. If the market shifts Corey and Sally will save less by getting the credit.

The Decision

As I mentioned, a home buying decision is far bigger than finances. Your home impacts your time, the quality of your kids' friends and education, and several hundred other things.

In most cases, I'll make an argument that small savings add up to significant amounts over a lifetime. When we're talking about cutting a coke a day to save an extra $25,000 over the next 30 years, I'll argue for cutting the coke.

In this case, I'm taking the opposite approach. I'm recommending cutting the coke each day for the next 30 years instead of taking the federal tax credit. Corey and Sally won't get $8,000 today, but in the long run they'll most likely be happier with a well planned and analyzed house buying decision that costs them an extra $16,000 over the next 30 years.

If you've come this far, you're on your way. Tomorrow we'll talk about how to improve your cash flow by managing expenses.

If you've come this far, you're on your way. Tomorrow we'll talk about how to improve your cash flow by managing expenses.